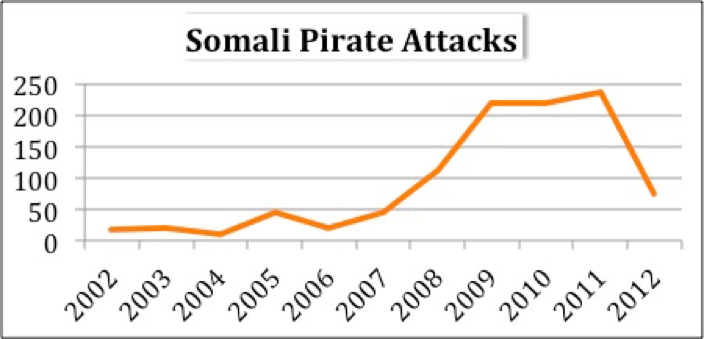

(Data from ICC International Maritime Bureau – Piracy And Armed Robbery Against Ships Reports from 2004-2012)

The most financially lucrative form of piracy in the modern age has been hijack-ransom. While structural conditions – state weakness, existence of organized groups, and proximity to high value vessels – allowed the development of Somali piracy, it was their innovative technique that made them successful. Techniques can, and often do, spread, which begs the question: can ransom-hijack model piracy spread and if so, where?

Innovation diffusion theory is a useful framework for understanding how hijack-ransom piracy might spread. The concept explains how innovations proliferate through networks. There are five characteristics of an innovation that make it more or less diffusible: relative advantage, compatibility, trialability, observability, and complexity. Looking at the first four characteristics, hijack-ransom piracy comes out as easily transferable. The relative advantage—high profitability and low risk—is obvious. The technique is compatible with the practices and equipment available to most maritime criminal groups. And because it does not require extensive retooling in terms of gear, hijack-ransom piracy is trialable. A group can try this type of piracy and if they don’t like it, revert to their previous operational model without much lost investment. Lastly, the Somali style piracy is easily observable—it happens in the open and garners worldwide press coverage. Any group thinking of adopting the method will see numerous examples of the success of hijack-ransom piracy.

It is the last characteristic, complexity, which potentially hinders the diffusion of Somali-style piracy. The infrastructure necessary to support hijack-ransom piracy is more complex than is commonly assumed. In addition to the intricacy of the operations themselves, hijack-ransom pirate organizations require a number of key specialists, in addition to the foot soldiers that make up the bulk of the groups. They need negotiators to communicate with shipping companies to secure ransoms. Logisticians ensure that adequate food, water, and qat are available for a prolonged hostage situation. Finally, sustaining pirate operations, during the commandeering phase, and especially during the hostage state, is expensive, so investors are required.

The complexity of hijack-ransom piracy means that any diffusion of the technique must include the transfer of both tacit and explicit knowledge to potential adopter groups. Tacit knowledge is expert knowledge that is not easily expressed. For example this would include the knowledge of how to find a valuable ship, how to keep hostages alive, and how to negotiate with an international shipping company. Explicit knowledge is direct and easily expressed knowledge. Explicit knowledge is the operational knowledge an adopter could gain from reading a descriptive newspaper account of a pirate attack. Tacit knowledge, on the other hand, can only be transferred directly from an expert to a new user.

Knowledge is transferred through two types of communication channels: mass and interpersonal. Mass communication is unidirectional and reaches large, heterogeneous audiences. It includes such mediums as newspapers and television. Interpersonal communication is interactive and takes place between individuals or in small groups. Explicit information travels effectively and swiftly via mass communication channels. There has certainly been enough coverage of Somali piracy in the international press to provide a potential adopter with all the required explicit information. However, explicit knowledge alone is not sufficient: without tacit knowledge a pirate group will not have enough information to adopt hijack-ransom piracy. For innovation to spread, both explicit and tacit information must reach a potential adopter.

Tacit information is transmitted via interpersonal channels, which are interactive, allowing for back and forth between a potential adopter and a current user. Interpersonal interaction mostly occurs between people who know each other, or in other words, individuals or groups that share common characteristics: religion, ideology, ethnicity, or geographic proximity.

Therefore, in looking at the locations where hijack-ransom piracy could spread, one of the key markers is the existence of actors who have network connections to Somalia’s pirate groups. These actors are the ones that Somali pirates interact with most frequently and are positioned to receive the tacit knowledge necessary to adopt Somali hijack-ransom piracy. There are two likely networks through which Somali piracy might diffuse: the Somali Diaspora and Al-Qaeda linked groups. The Somali Diaspora is global, though it has concentrations in East Africa, Europe and the U.S. There is anecdotal evidence of connections between Al-Qaeda (and affiliates) and Somali pirates, and there is certainly enough circumstantial evidence to assume that information passes between the groups. Additionally, the areas of southern Somalia under Al-Shabaab control represent the largest area “held” by an Al-Qaeda affiliated group, and have attracted a host of international militants.

In addition to looking at areas with pirate-linked network presence, we also looked at areas with the structural conditions in place to support hijack-ransom piracy. These are: state weakness, existence of organized groups, and proximity to high value vessels. Pirate groups must have a secure area to organize and a harbor to secure the hijacked vessel without fear of interdiction. They do not require a completely failed state, merely ungoverned coastal territory in which they can operate unhindered. The complexity of hijack-ransom piracy makes the presence of organized armed groups necessary for piracy to be effective. These groups have the organizational and financial capital necessary to carry out sophisticated hijack-ransom pirate operations. And most obviously, pirate groups must be located near high value shipping. Hijack-ransom piracy takes the revenue-generation capacity of a vessel hostage, so pirates need to be near not just international shipping, but high value vessels to make the enterprise worthwhile.

To find potential diffusion areas, we overlaid the two sets of vectors (structural conditions and Somali pirate networks) and looked for areas where all the factors intersected. We found four areas to which Somali piracy could potential spread. The first is in Southeast Asia, primarily in Indonesian, Malaysian and Filipino waters, which have a long history of piracy and a high concentration of global shipping. The region has several Al-Qaeda affiliate organizations, which have a history of sending personnel to various Al-Qaeda operational theaters. The second is the Gulf of Guinea, which has recently seen a spike in piracy, although thus far not the hijack-ransom variety. The region hosts a number of organized militant and piratic groups who would likely be interested in the technique, as well as the presence of Boko Haram, which is believed to have received some training in Somalia. The third is the Strait of Hormuz; however, the proximity of this area to Somalia increases the likelihood that pirates interested in operating around the Strait will opt for bases in Somalia. The last area is the Libyan coast, which is close to high value global shipping going through the Suez Canal. Despite being proximal to developed countries with powerful navies, Libya has all the factors to make it susceptible to hijack-ransom piracy: the state is weak, and there is a concentrated presence of organized crime groups, many of which are associated with Al-Qaeda. There is even a Somali Diaspora presence in the area associated with illicit maritime activities.

It’s important to highlight what this analysis is and is not. It is not intended to be a Magic 8 Ball, able to predict precisely if and where hijack-ransom piracy where emerge. Neither should it be read as an assertion that the Somali Diaspora, or, for that matter Al-Qaeda members, are all latent pirates. They are not. However, they do represent networks with strong internal communication that could facilitate the spread of knowledge between disparate regions. With this analysis, we have tried to think critically about how Somali model piracy could spread, what conditions may facilitate it, and the role of various networks in the diffusion of the innovation. The utility of pinpointing areas at risk – such as the Gulf of Guinea and Libya – is that it enables national governments and the international community to proactively work to mitigate the chance the technique might emerge. Sound policy and well-designed aid programs can address some, though not all, of the structural factors – state weakness and the ability of organized crime groups to operate with impunity – as well as some of the mega-trends – inequality and societal dislocation – which foster piracy in the first place. Such proactive policies are expensive, but they are a fraction of the tens of billions of dollars which hijack-ransom could annually cost the global economy.